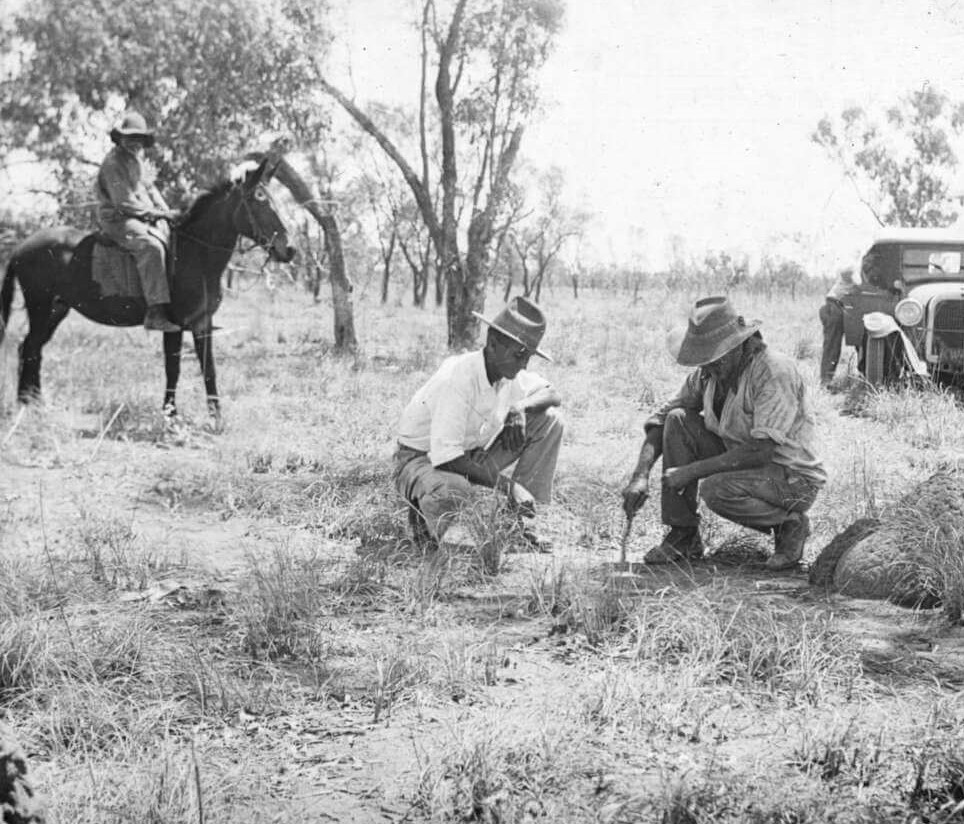

Remote A.I.M and Flying Doctor Service nurses and doctors were exceptionally mobile and travelled huge distances. For example, Sister Myra Blanch was responsible for a region which spanned 700 km east-west from western NSW to Lake Eyre and 1040 km north-south from the Queensland channel country to the Murray River. Sister Blanch was the first nurse employed by the Flying Doctor Service and was based in Broken Hill between 1945 and 1954. She traversed her region by plane, with the Flying Doctor Service pilot, and alone by car. Beyond the main roads, routes – such as the road between Innamincka and Birdsville pictured below – were rough and ill-defined, rarely signposted and little more than tyre tracks in the sand.

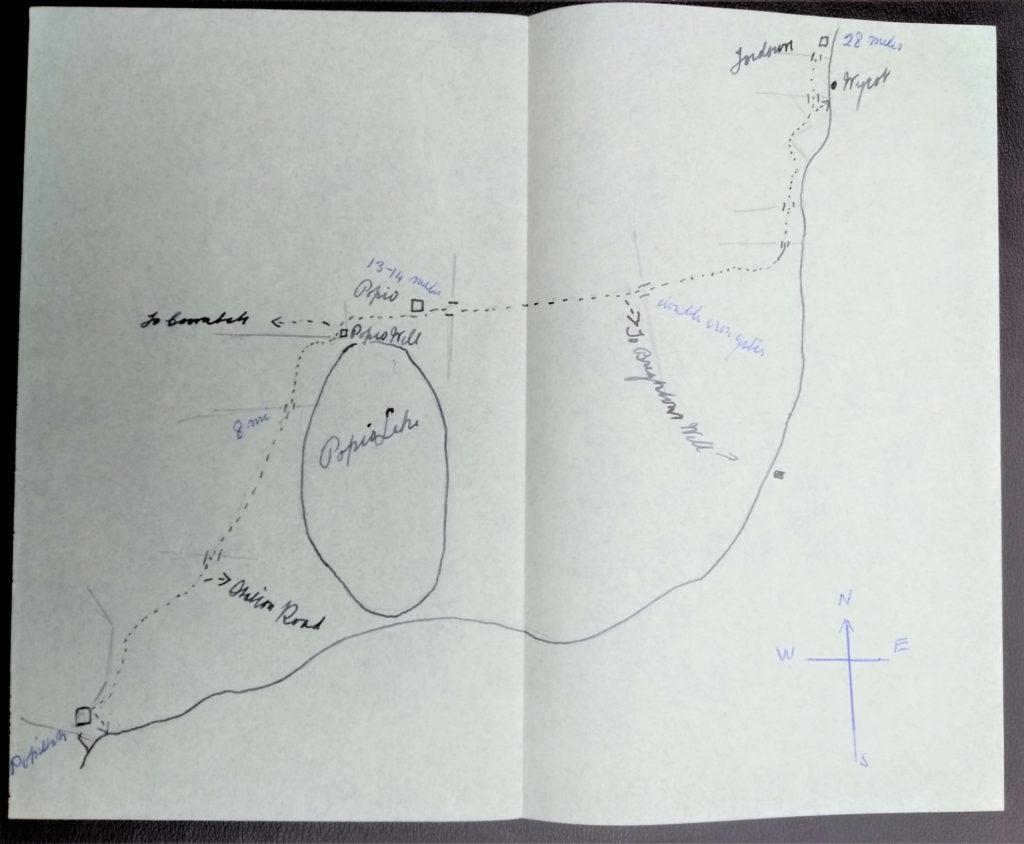

Maps to navigate between stations were developed ‘on the run’. At each station Myra Blanch received directions for the easiest and most practical route to her next destination. Sometimes a station worker or mailman would escort her part of the way, but more often, rudimentary maps were drawn to guide her travels. In December 1949, Myra wrote in her monthly report of travels between stations in the NSW South Australia border area: ‘Parts of track are very rough, particularly if going around a newly formed lake. I can see the telephone wire which the road normally follows plunging into the lake, and can just barely make out where it emerges’.

Sister Myra Blanch used rudimentary paper maps such as this one showing the route between Popiltah, Popio, Wycot and Tor Downs Stations to the west of the Broken Hill – Wentworth road. These maps were carefully drawn showing easily identifiable landmarks such as a lake, river, gates and track diversions. The map is not drawn to scale but shows the points of the compass to help orientation.

Roadways in the remote outback became ephemeral during wet, windy and particularly dry weather, appearing and disappearing with the flow of sand and water. In May 1950, after very heavy rains, Myra described traversing a track on the edge of the Strzelecki Desert in South Australia: ‘The only really bad piece of road was just not mentioned on my “mud map”. The road just ran into a lake of water left by rains in March and didn’t come out and only one other vehicle had been through [the area] since March. I had to find another way through and pick up the road on the other side of the lake.’

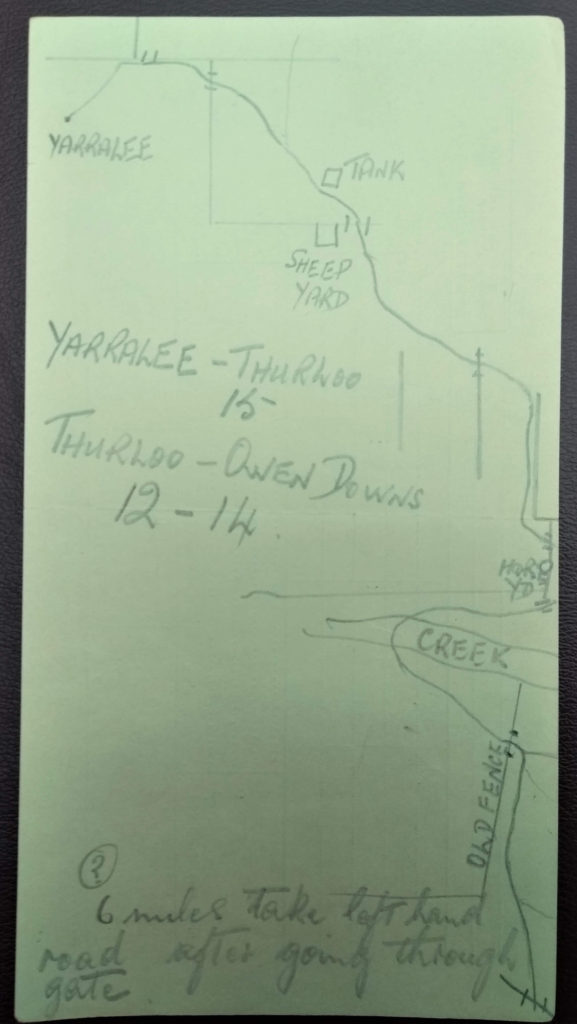

‘Mud maps’ were drawn on easily accessible and transportable scraps of paper such as the reverse side of a telegram slip. This map of tracks near the NSW-Queensland border was likely drawn by a station worker to guide Myra Blanch from Yarralee, to Thurloo and Owen Downs. The relative location of water tanks, sheep and horse yards, dry creek beds and fence lines, and their relationship to each other, were part of the detailed mental maps which pastoralists had for their landscape.

Sister Blanch quickly became familiar with the routes she traversed and had a large collection of mud maps in her briefcase to guide her to rarely visited stations. On one particularly bad stretch of road near the NSW-South Australian border in November 1946, Myra described the necessity for ‘sand charges’ to ascend the hills. During one of these charges some equipment, including Myra’s briefcase containing maps, bounced from the car. The following day, a boundary rider found some of the lost equipment, but the briefcase was lost in drifting sand.

Station names and directions to nearby landing strips were painted in large letters on roofs to assist pilots, In the early years of the Aerial Medical Service, pilots, like nurses, relied on landmarks such as river beds, sandhills and large buildings to aid navigation. After the Second World War the Flying Doctor Service used detailed RAAF maps, however roof identification to assist pilots, still remains common in remote areas.

Travel accounts of A.I.M and Flying Doctor Service workers in the 1910s to 1950s read as odysseys of triumph; overcoming floods, sand drifts, broken axels, and dust storms. Doctors, nurses and pilots took great pride in cheerful resourcefulness and resilience. This was an image which the organisations encouraged in their remote workers.