The Australian Inland Mission was founded in 1912, in the shadow of Federation, and its early maps of Australia were visual affirmations of a new nation, its boundaries and its unity. As these maps show, the A.I.M saw itself as crucial to the project of nation-building in three ways: assisting settlement of the underpopulated remote inland; building a frontier identity for Australia; and unifying a nation.

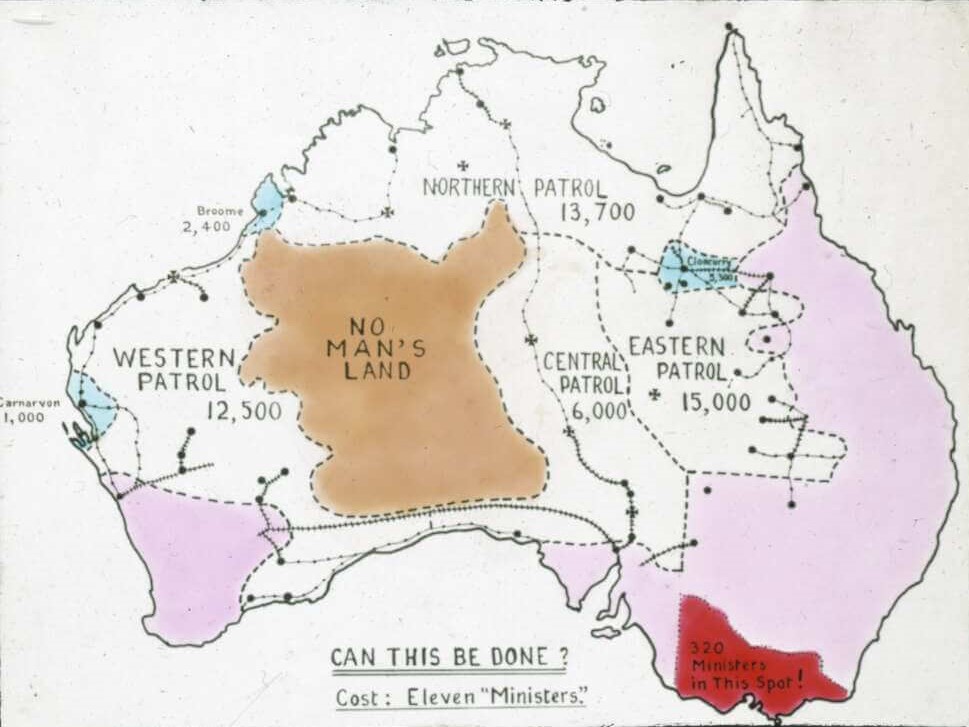

No Man’s Land

This 1910 lantern slide is the earliest map in the A.I.M collections. A huge brown area at the heart of the continent is the glaringly obvious feature of this map. ‘No Man’s Land’ falls between or outside jurisdiction and control. Its naming on this map suggests that this area is devoid of human habitation, or more accurately devoid of white permanent settlement. In an era of official preoccupation with race and skin colour is it a coincidence that the tone used to designate ‘No Man’s Land’ is brown?

‘Patrols’, the word used to indicate the regions serviced by A.I.M clergy, suggested an element of protection as well as the peripatetic nature of the ‘patrol padre’. Concern with security was influenced by fears of external threat such as invasion of a sparsely settled land, as is discussed further below.

As we will see, concern for the ‘emptiness’ of the interior is a feature which recurs in A.I.M maps throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

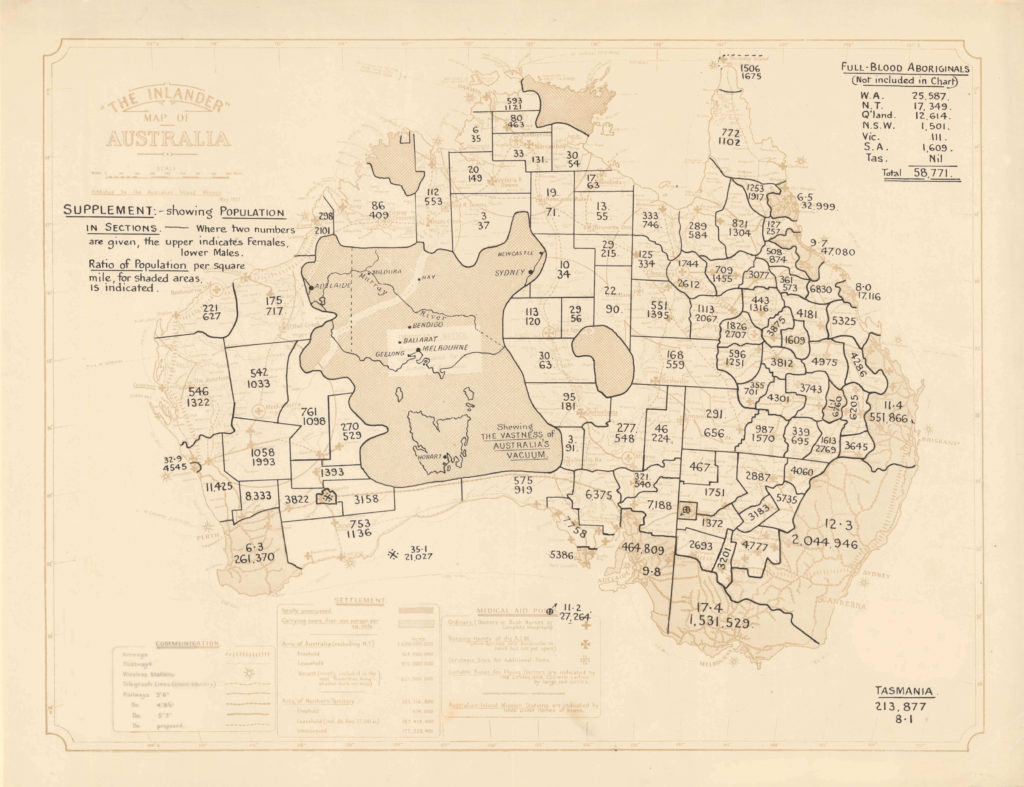

In 1922, ‘No Man’s Land’ is described as the ‘vastness of Australia’s vacuum’. A vacuum implies there is a danger of collapse to nothingness, as alarmist a concept as ‘no man’s land’. The maps of Victoria and Tasmania, inserted into the boundaries of ‘the vacuum’ reinforce its vastness, and perhaps thereby its need for protection.

On this map, the populations of different regions overlay the faint outlines of communication routes, medical and postal services and settlements. This map starkly reflects contemporary preoccupations with populating northern and inland Australia and with fears of invasion by other cultures or colonial powers. In the early 1920s, Australia was still a new nation, which had just emerged from the destructive jostling for power and imperialism which led to the First World War. In this period, populating the inland was as much about safeguarding the nation against future invasion and asserting possession of the country as it was about economic development. The A.I.M had patriotic aims in supporting the inland population of British Australians.

As symbolic representations, all maps are syntheses and intensely selective images conveying particular and partial messages. We can see the population map of 1922 has some notable absences. In the top right corner of the image is a list of the population of ‘full-blood Aborigines’ in each State. These figures have been deliberately excluded from the map itself, despite amounting to an estimated 58 771 people. Similarly no population is given for regions such as Arnhem Land where most inhabitants in the early twentieth century were Aboriginal.

Indigenous people are absent from most A.I.M and Flying Doctor Service maps, as they were not, at the time, considered to be part of the nation, were dehumanised and more akin with ‘No Man’s Land’. In the early years of the AIM, the organisation clearly stated that its interest lay with white settlers in remote areas (as the notes on the 1917 map below also state). Although Aborigines were treated by A.I.M nursing and medical staff free of charge, and they participated in other A.I.M programs such as kindergartens, the organisation viewed Indigenous people as incidental rather than central to their concerns. Many nurses and doctors were sympathetic to Indigenous people in their area, however the organisation felt that ‘full blood Aborigines’ were catered for by a separate Aboriginal Mission system (as noted on the 1917 map below).

Maps have long been agents of colonisation – laying claim to authority and territory and defining boundaries. In an indirect way, A.I.M maps were part of this process. As a promoter of white settlement in the inland in the early twentieth century, the A.I.M was complicit in excluding and displacing Indigenous people from their land. As a product of the dominant culture, these maps inevitably make no acknowledgement of the song lines, pathways and symbols by which Aboriginal people mapped their country.

The 1922 population map (like the 1910 map) has another notable omission: the island of Tasmania. Its population of 213 877 is listed separately in the bottom right corner of the sheet, while the outline of Tasmania appears, drifting and unanchored, in No Man’s Land. Tasmanians, like Aborigines, are seemingly landless and ungrounded. The omission of Tasmania from the outline of the continent, and from many other A.I.M and Flying Doctor Service maps, at its simplest, reflects the absence of A.I.M and Flying Doctor Services in Tasmania. A.I.M nursing clinics never operated in the island state and, in 1960, Tasmania was the last state to establish a branch of the Flying Doctor Service, over twenty years after the other States. More fundamentally the absence of services in Tasmania, and its corresponding absence from maps, reflect a particular, romanticised vision of remote Australia as arid inland plains and deserts sparsely dotted with coolabah trees and billabongs rather than the mountains, rushing rivers and thick, damp forests of western Tasmania.

A Frontier Identity

‘Think all round and right through. Incorporate your country in your life, and work and prayer’ exhorts the A.I.M on the reverse side of a map printed in The Inlander in 1917. This map, like all of the A.I.M promotional maps was created for audiences distant from the A.I.M’s patrols. Their goal was to create an image of the outback in the minds of ‘insiders’ – the term used by historian C.E.W Bean and others to describe people living in densely settled areas, as opposed to ‘outsiders’ who live in remote regions.

The recruitment of an Inland Brigade of AIM supporters attempted to engage the sympathy of people in populous areas for remote settlers and create links between the two worlds. An important part of this promotion was to insert the A.I.M and its work into the thinking of ‘insiders’, encouraging Australians to care, not only about the organisation, but also for the settlers themselves. Flynn’s ambition was to encourage an Australian identity which embraced the remote, a goal he was, over time, exceptionally successful in achieving.

The upside down map of Australia with Great Britain inserted in its borders, again reinforces the vastness of the region serviced by the A.I.M.

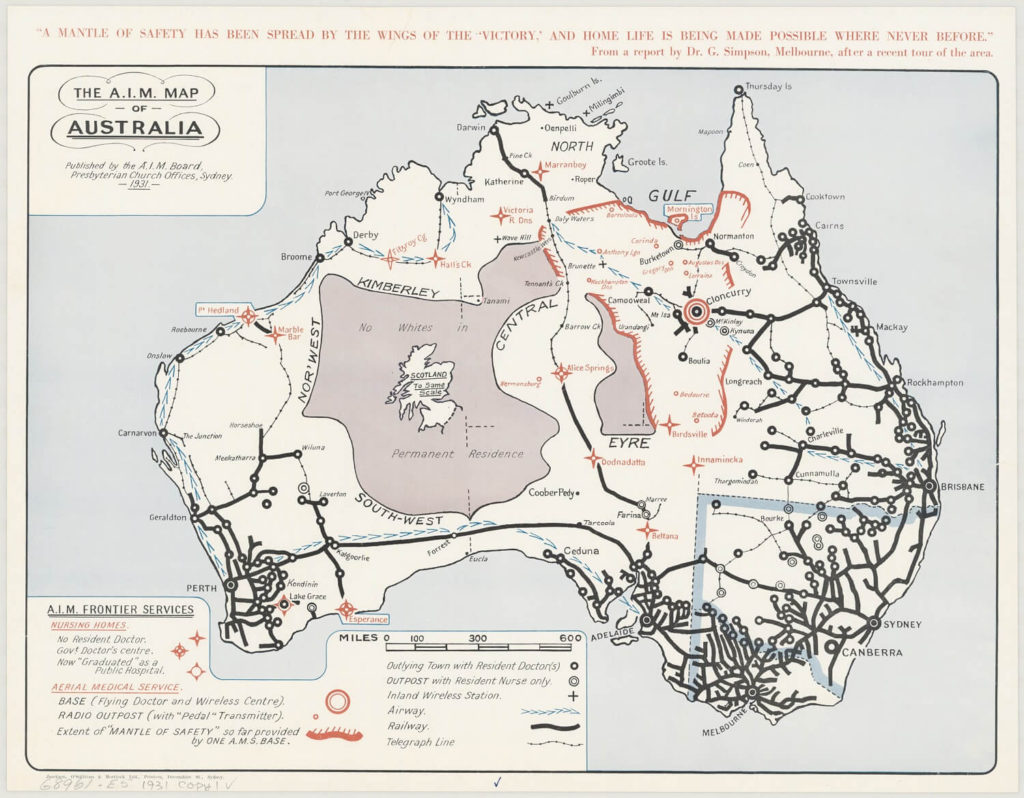

The red ‘frontier lines’ marking the extent of A.I.M influence are prominent features of this 1931 map. These lines acknowledge that ‘No Man’s Land’ (now named ‘no whites in permanent residence’) remained, as yet, unreachable but illustrate that the A.I.M was pushing the boundaries of this unknown. This map is among the last to clearly identify the ‘uninhabited’ region at the heart of the country. The concept of a frontier was vital to the A.I.M vision, as discussed by historian Brigid Hains: A frontier, she writes, was not something to be obliterated but accommodated and celebrated; a challenge waved to the rest of the nation. Frontiers held promise, possibility and romance and the goal of the A.I.M was to make it integral to Australian identity.

The Mantle of Safety (quoted at the top of this map) was a phrase coined by John Flynn in 1927 to describe the combination of nursing clinics, air transport and radio communication which would provide care to settlers of remote areas. This mantle, Flynn believed would transform the inland from a frontier of temporary restless men, to a permanent settlement of families.

Unifying a Nation

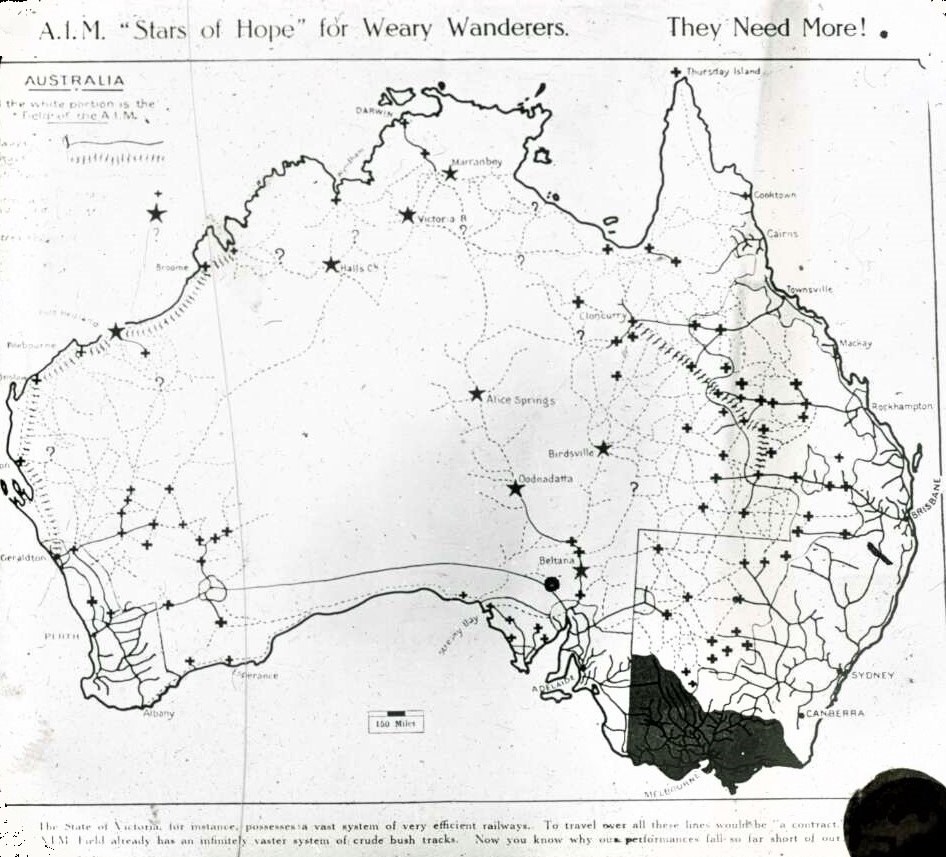

‘”Stars of Hope for Weary Wanderers” is the description of A.I.M nursing clinics in this mid 1920s lantern slide. Here, A.I.M nursing clinics are beacons in an interior otherwise largely devoid of services. Improving health and social services in remote areas was a way in which the A.I.M attempted to unify the nation and, in this period, it was particularly preoccupied with a lack of infrastructure in remote areas. Like the 1910s map and many others produced by the A.I.M in its early years, it compares the vast, under serviced inland Australia with well serviced Victoria. The intricate railway networks of Victoria, eastern NSW, south eastern Queensland and Adelaide area are compared to the ‘infinitely vaster’ system of crude bush tracks in the outback.

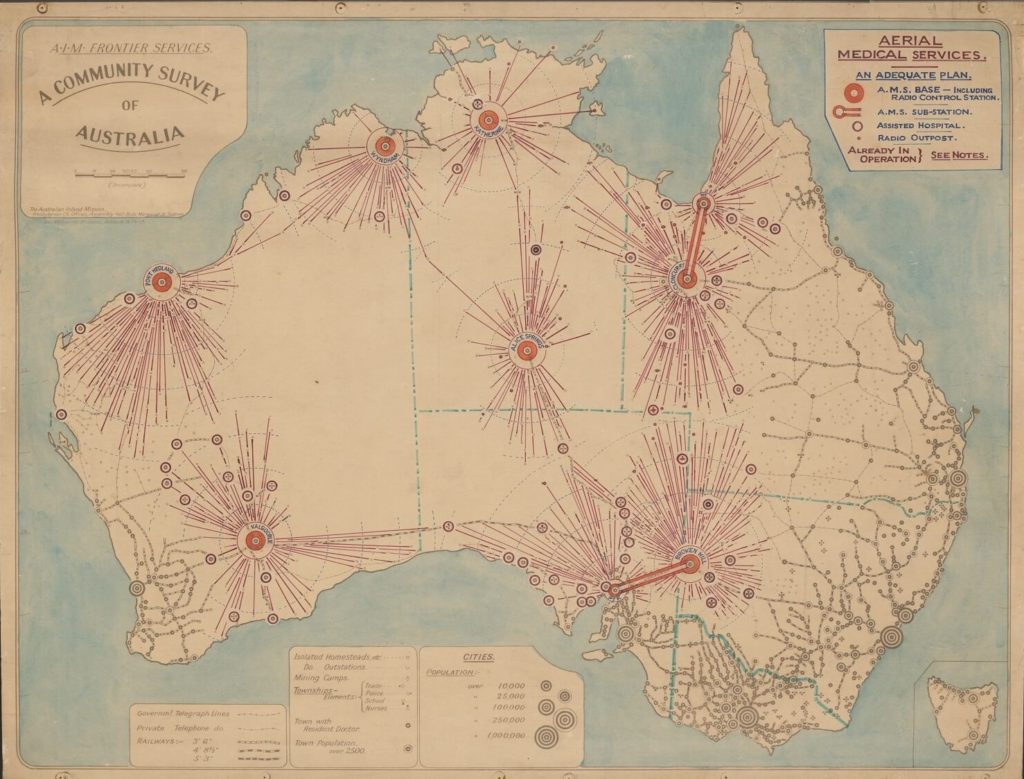

The A.I.M and Aerial Medical Service always considered themselves to be national programs. On this 1934 map, state boundaries are marked but are irrelevant to the organisations’ activities, with the aerial reach crossing state borders. Air and radio services are illustrated as bright lights sparking across the nation, reducing rail and telegraph to a shadowy background.

The A.I.M’s sinuous patrol routes appear as the country’s arteries and veins, infiltrating the interior tying major cities to faraway places and binding ‘our loneliest frontiers and our busiest cities’ in this 1930s paper map. The map suggests that A.I.M nurses, doctors and padres facilitated this bond.