Maps produced by the A.I.M and Flying Doctor Service from the end of the 1930s to the early 1960s shifted in emphasis. They increasingly portrayed the organisations as conduits of civilization and modernity while messages about population growth and settlement, so dominant in early maps, became more subtle. Again, this reflected the national ethos in Australia in the mid twentieth century.

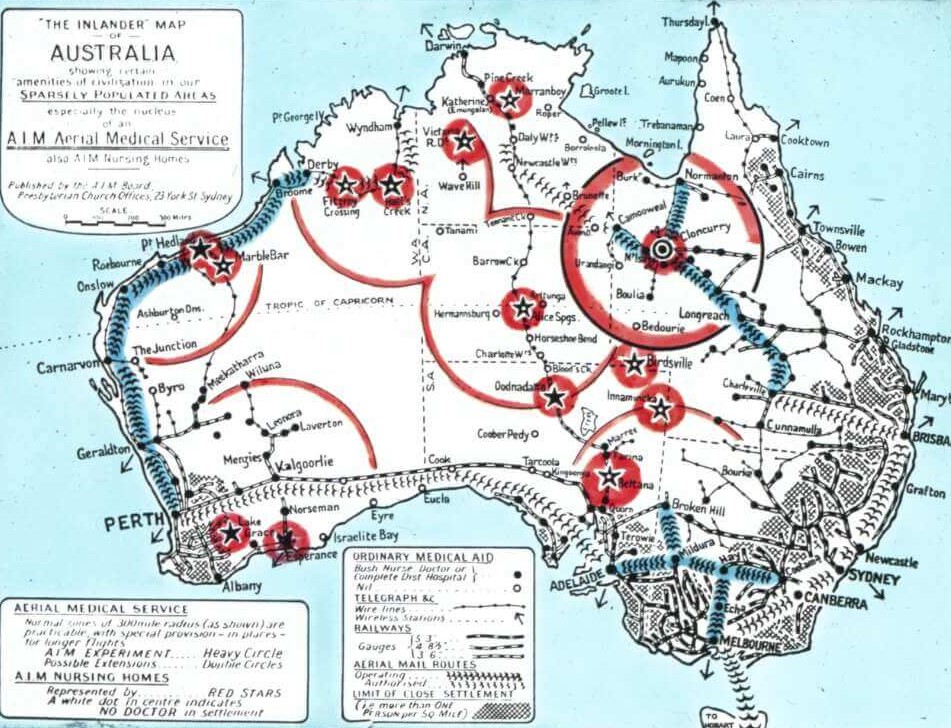

The principal conduits for conveying ‘the amenities of civilization’ were the Aerial Medical Service and the A.I.M, this late 1930s lantern slide suggests. Tendrils of rail, telegraph and aerial mail routes emanate from closely settled regions, pushing into the blank space of the interior; but it is the bright red and black stars of the A.I.M and the bold red circles of the Aerial Medical Service which dominate this process as the reach of the Aerial Medical Services form clear lines penetrating the unknown.

Unlike government maps which were concerned with claiming territory for economic, strategic or political reasons, the A.I.M promotional maps reflected the A.I.M goal of cultural infiltration. The A.I.M’s concern was to bring to the settlers of the inland all the markers of civilization: medicine, science, hygiene, technology, Christianity, literature, order and expertise. Settler women’s well-being was a particular focus for the A.I.M and its nurses formed a bridge between domesticity and science. A.I.M nurses became models of homeliness in the outback and their clinics were known as nursing ‘homes’ which offered a haven of warmth, comfort and compassion. In their role as public health advocates, nurses attempted to bring women’s domestic work environment into line with science and medical advice, supporting, improving and rationalising women’s skills in hygiene, nutrition, mothercraft and housekeeping.

There are no maps from the 1940s in the Australian Inland Mission and Flying Doctor Service collections due to Second World War restrictions.

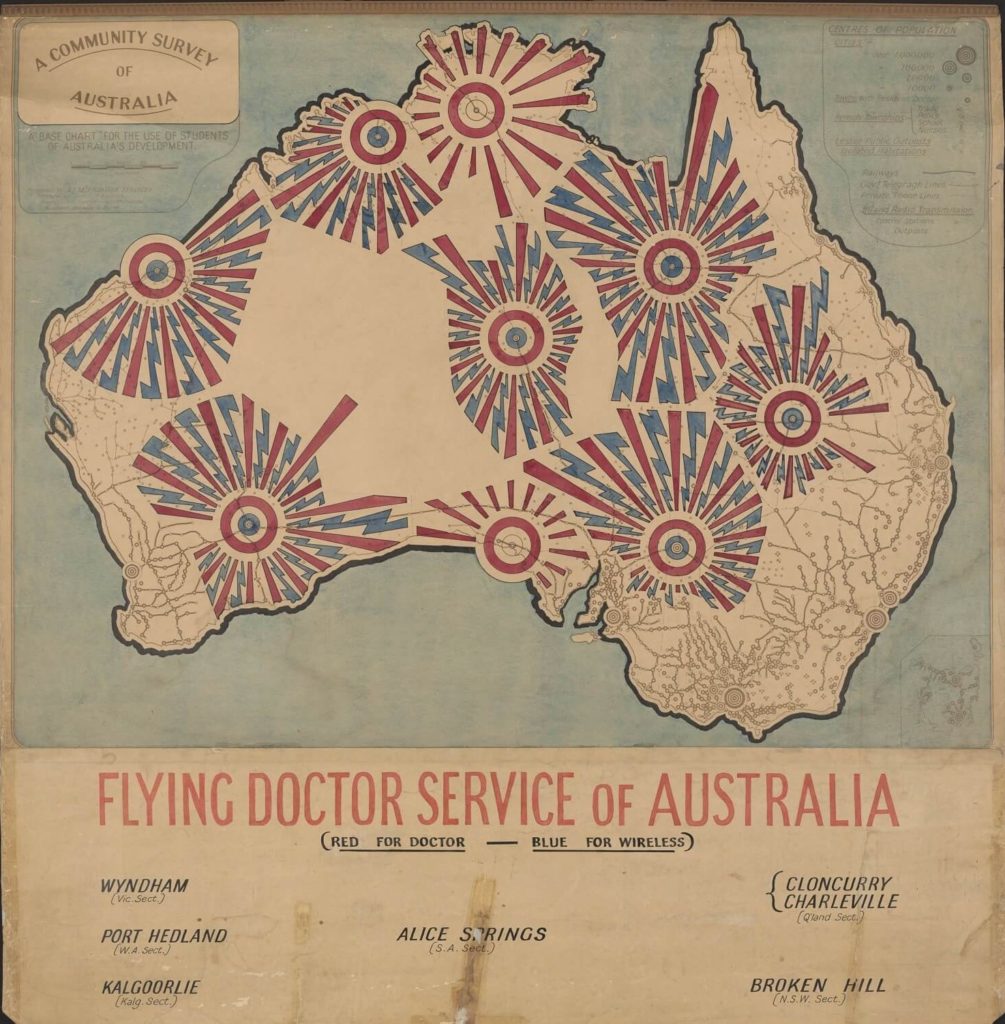

This Flying Doctor Service map from the 1950s is bold in its depiction of the reach of medical and wireless services. Hand coloured in patriotic red and blue, Flying Doctor Services penetrate the inland and dominate the markings on the base map. The aggressiveness of the colours and assuredness of the lines contrast with the fluidity and pastel tones of the early A.I.M maps. These contrasting approaches reflect the differing ideologies of the two organisations.

The A.I.M’s mission for improving the physical, emotional, social and spiritual wellbeing of remote settlers were complex and multifaceted. Linked to its A.I.M to improve the physical and emotional wellbeing of settlers, the A.I.M had a communitarian ideology which promoted both local social interactions and an integrated national identity. Nurses and clergy lived among the people they served providing medical and spiritual care, conducting public health education, emotional counselling and facilitating social connections. The tasks of an A.I.M nurse (all of whom were women) was exceptionally diverse and ranged from pulling teeth, diagnosing diseases and dispensing medicine, to running kindergartens, distributing literature, convening women’s groups and organising festivals. Nurses needed to fit in with the communities in which they lived and be fluid and flexible to local cultures.

By contrast, the Flying Doctor Service (staffed mostly by men) performed emergency medicine and acute health care. Doctors’ connections with remote communities was at arm’s length and Flying Doctor bases were in regional centres such as Cloncurry, Broken Hill and Port Hedland distant from patients. Doctors and pilots flew in, performed their tasks and flew out, or evacuated patients to cities. In contrast to the broader cultural influence of the A.I.M, the image of the Flying Doctor Service was technological, relying on the twin technologies of aeroplane and radio.

By the early 1950s, Australia was becoming a prosperous and optimistic nation. Although in many ways still conservative and insular Australia identified with youthfulness, modernity, science and technological development. The wool boom, combined with high prices for other agricultural produce and largely clement weather meant that rural white people, like their counterparts in the city, enjoyed improving living standards and were embracing the plethora of newly available domestic amenities such as fridges, Mix-Masters and cars.

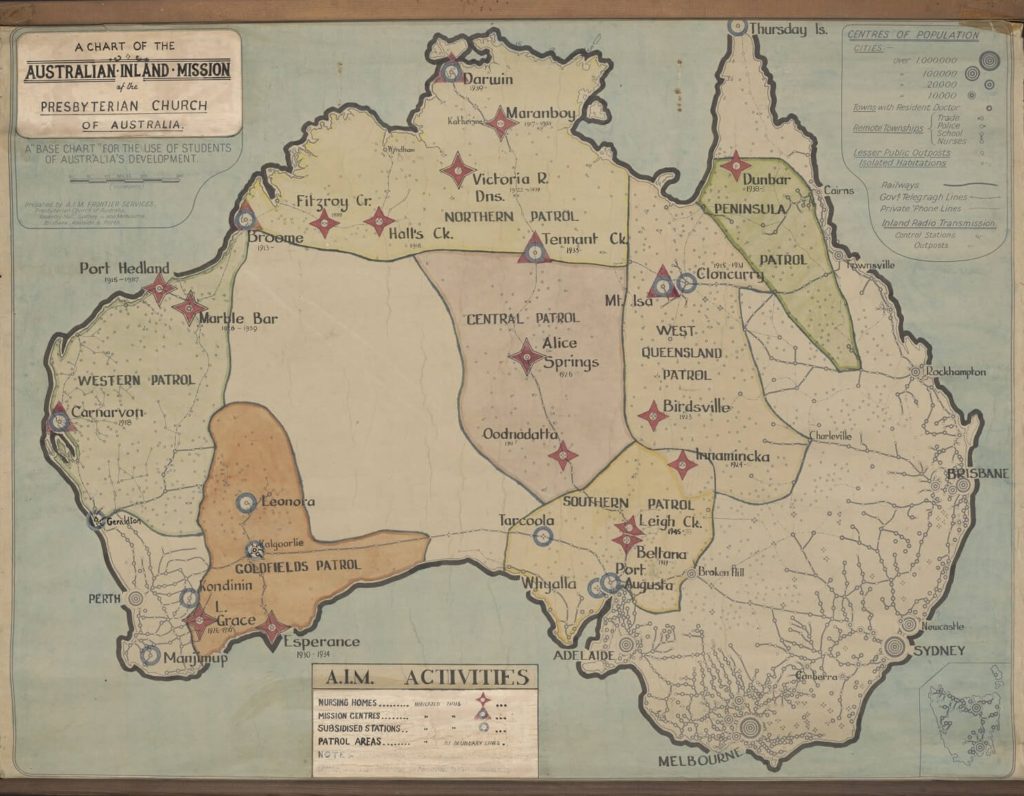

This national confidence is reflected in the large 1952 wall chart of A.I.M activities. This map shows the A.I.M to be a well-established organisation overseeing health and wellbeing in nearly two thirds of the continent. The subtitle of the map ‘A base chart for the use of students of Australia’s Development’ links the A.I.M activities to the progress of the nation. Now there is less emphasis on the frontier and more on the ‘mantle’; although a line still divides the ‘settled’ from the ‘unsettled’. A.I.M patrols are solid blocks of colour and influence rather than point-to-point inroads into the unknown.

The red and blue stars, triangles and circles of the nursing homes, mission centres and subsidised stations imply a somewhat greater A.I.M presence in the inland than was actually current, as small dates beneath the shapes reveal that at least seven stations in the northern, western, goldfields and west Queensland patrol had either closed or been transferred to another authority (such as the Flying Doctor Service which was now a separate, government funded organisation).

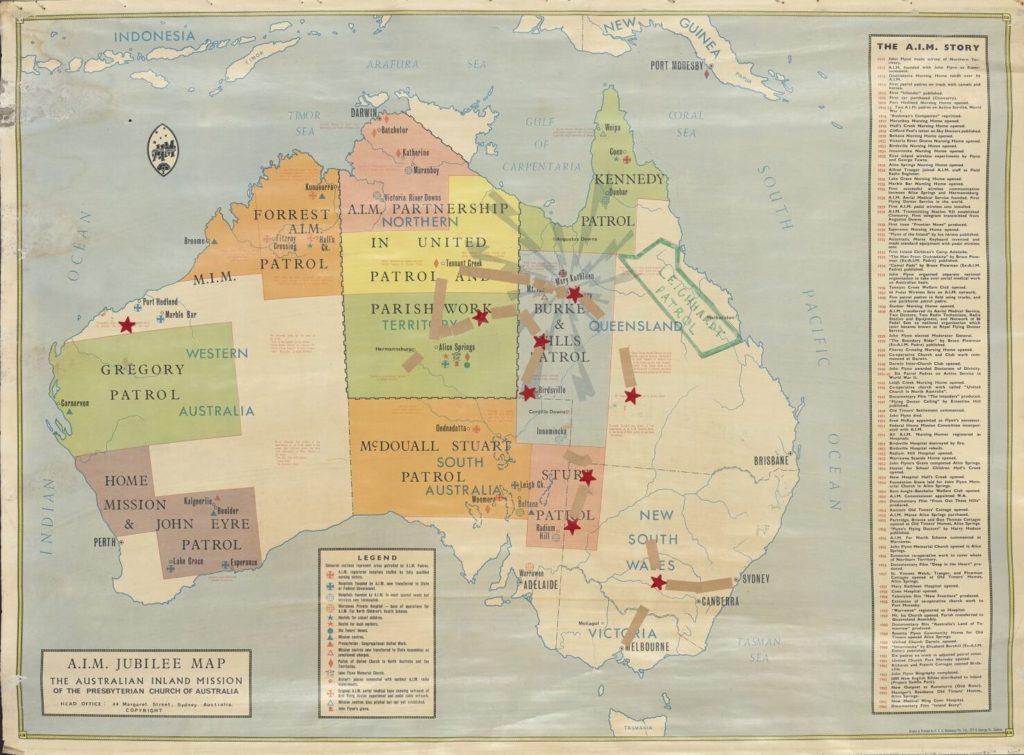

The Jubilee map, the final image in this essay, is a celebratory story-map narrating the history of the A.I.M. Salient features of the A.I.M development are presented as ‘the A.I.M story’, each item confirming the legend of Flynn and the A.I.M, now well-known in Australia. Typed notes within the borders of the continent provide further information about the A.I.M and its workers and link the organisation to future national development such as the construction of ‘beef roads’ across the continent. The ‘blank space’ has retreated still further. Unlike earlier hand coloured maps with fluid lines, this map has the definite lines of a printed image which lends the organisation additional authority. In reflecting on the fifty years of A.I.M activities, this map presents the organisation as a project with a history which has come to fruition. Remote, untamed Australia remains a celebrated part of the nation but is now, firmly bonded to the settled world through the amenities of the A.I.M. The A.I.M has claimed and developed the remote inland.